Recently, Travis Thieman and I gave a talk to the CTO School meetup group in NYC about our experiences moving GameChanger’s mainly Chef-based build and deploy pipeline to one based heavily around Docker.

In this post, I want to dig a little deeper into one of the topics we covered: how Docker has enabled us to position our engineering team to scale out in a manner which would have been inconceivable with a more traditional CM tool like Chef, Puppet or Ansible.

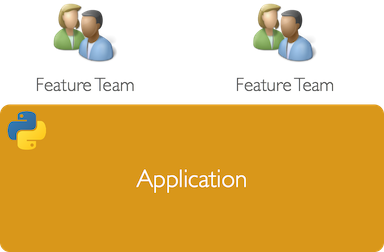

From seed to monolith

GameChanger’s backend started out as 100% Python - a Django app with some rudimentary features running on AWS. At this sort of scale, build and deploy typically looks pretty simple - some form of manually-run hand-rolled script which pulls master and restarts some services. There’s really no need for anything more complicated than that when you’re iterating quickly on new features.

Our team grew and our app acquired more and more responsibilities. Our backend was still built on Django and we were still deploying using hand-rolled scripts but with a little additional help from Fabric to automate the process across an increasing number of servers.

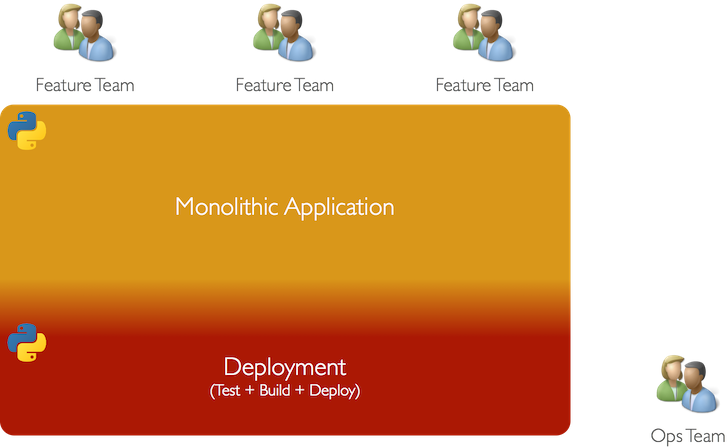

This growth continued. About 18 months ago our backend had organically grown into a large monolithic application with far too many responsibilities each with different operational characteristics and desired SLAs.

At this scale, the hand-rolled script approach to deployment had become unsustainable and we’d formed a dedicated Ops Team simply to own the process of shipping our code to production.

The Ops Team

Our Ops Team started out with a pretty simple mandate: the creation of a build and deploy pipeline which enabled separate teams of developers to all push new code to production without needing to care how.

We built a deploy system based around Chef with numerous roles and cookbooks which allowed us to build and reconfigure the various flavours of servers we needed. (As it turns out, we determined that Chef actually created a number of deploy-time risks which started to add up as our cluster size increased, but we’ll save that for another day.)

With our tech stack almost exclusively Python-based, having the Ops Team completely own our deployment pipeline was sustainable as the knowledge the team needed to do their jobs remained fairly static.

The Development and Ops teams worked very closely making it possible for responsibilities and knowledge to be shared - developers made Chef changes, ops engineers changed application code. In essence we were adhering to “DevOps” principles.

From monolith to microservices

About 12 months ago, we realized we needed to make a radical strategic change to our stack. The huge monolithic system which we’d built over time was showing real growing pains:

- Indirect coupling between functionally unrelated components caused by shared dependencies (e.g. a common database).

- Fragility - A bug committed to one functional area could take everything down.

- Python, though a great prototyping language, inhibited our ability to build faster, more real-time functionality.

- Ownership boundaries between functional areas and shared components were fuzzy, with quality suffering as a result.

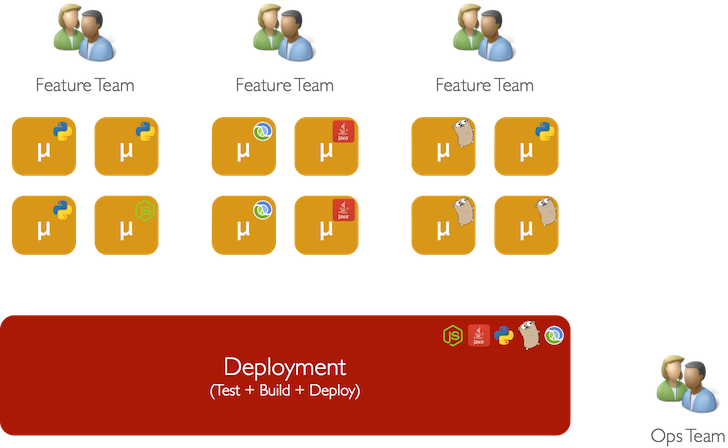

We realized that in order to continue to grow without these problems bringing our engineering velocity to a standstill, something had to change. That change was to transform our architecture to one based around microservices.

A deeper exploration of microservices architectures is beyond the scope of this post, but it should be relatively easy to see why shifting GameChanger’s stack to this kind of model made sense:

- Splitting each functional unit into its own service, with its own persistent store decouples functional units from each other and isolates failure.

- Each service can be built and scaled on a case-by-case basis matching the right language to the right problem.

- There is no confusion over ownership boundaries as each team has ownership over the services it maintains. Clear ownership incentivizes developers to take pride and improve quality.

But there is a problem - what happens to our Ops Team?

Having an Ops Team work closely with developers makes sense when the technology stack and hence the shared context is relatively static.

However, in a microservices world where teams need to make use of whatever technologies they need, this model starts to break down. Suddenly the Ops Team becomes overwhelmed with new technologies they need to figure out how to deploy and support. The amount of complexity they need to manage increases quickly and their productivity starts to fall as context-switching increases, and understandably there is pushback as delays are introduced.

In other words, with everything needing to go through an overloaded Ops Team, the cost of deploying a new service was high. Faced with this obstacle, our development teams would naturally take one of two paths to resolve the conflict:

- Implement their new feature inside one of the services or technologies already supported by the Ops Team.

- Bypass the Ops Team completely and roll their own deployment pipeline.

Option 1 is undesirable as it negates many of the benefits we’d identified as a motivating factor for moving to a microservices approach in the first place.

Option 2 seems like a better choice as it removes the Ops Team as a bottleneck and preserves the flexibility of teams to implement whatever technology they choose. However, having each development team take deployment “in-house” means that there is a lot of effort duplicated across teams (tooling, scripts, monitoring, etc).

Moreover, the development team is unlikely to put much effort into its deploy pipeline, they will do just enough to get their code to production - i.e. each team hand-rolling its own bespoke scripts. This is a problem as the maintainability, debugability, etc of our pipeline is likely to be sub-optimal as a result.

A third option?

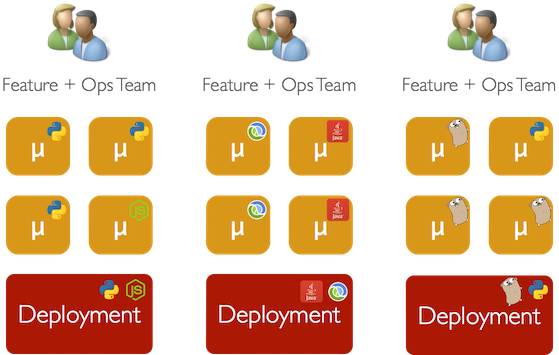

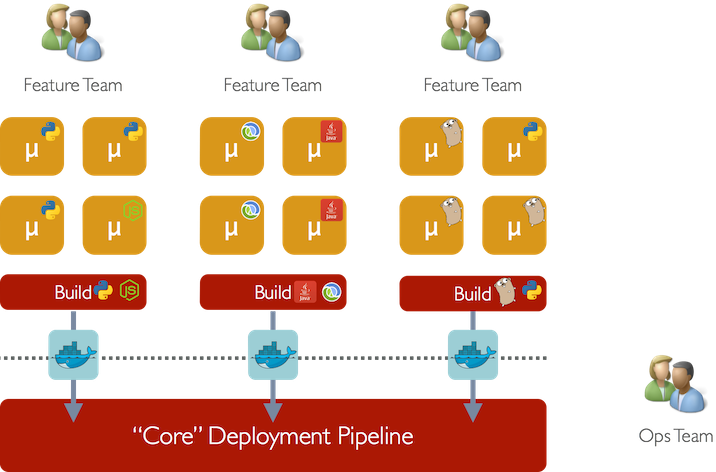

In an ideal world we’d want the best of both approaches: allow each development team to innovate and use whichever technology they see fit while continuing to have the Ops Team run the “core” build and deployment pipeline, insulated from impact of per-team technology choices.

Using traditional configuration management approaches like Chef, achieving this separation of concerns is possible in theory but extremely difficult in reality. We tried this at GameChanger and ultimately found that the mere fact we were trying to deploy applications to the same underlying host images lead to a plethora of non-obvious hard-to-diagnose problems.

A simple example: Services A and B are created by different teams and are both initially deployed against the node.js 0.10.0 binary using a Chef recipe. The owners of Service A require some of the new features in Node.js 0.12.0 to implement some feature and so attempt to upgrade the version of node.js deployed by the Chef recipe. This in turn breaks Service B which has not yet been updated to support 0.12.0.

This is a contrived example, but it shows that while using a CM tool like Chef there is inherent indirect coupling between each service’s deployment and the underlying platform. Without a centralized team to coordinate these kinds of upgrades, the process breaks down quickly.

What we really needed was an approach which isolated the concerns of service deployment from the concerns of platform deployment and reduced cost of deploying new services.

Docker: to the rescue

Docker allows each development team to implement services using whatever language, framework or runtime they deem appropriate. The only requirement they have to get their service to production is to provide a Docker image (plus some basic run configuration in a YAML file) to the Ops Team.

Luckily, creating a Dockerfile to build an image for a simple service is a relatively painless activity, especially when compared with performing the same task in Chef. Here’s what the Dockerfile for one of our node.js services looks like:

FROM docker.gamechanger.io/nodejs0.10

MAINTAINER Tom Leach

ADD . /gc/allegro

WORKDIR /gc/allegro

RUN mv Buildfile npm-shrinkwrap.json

RUN npm install

RUN mkdir -p /var/log/allegro

EXPOSE 80

CMD /usr/bin/node /gc/allegro/allegro.jsThis Dockerfile is simple to construct, simple to understand and will produce an image which can be run anywhere.

The Ops Team’s responsibilities are now restricted to simply building and maintaining a pipeline for deploying Docker containers without needing to concern themselves with what code each container actually contains. The contents of the Docker image are solely the responsibility of the development team. This allows the Ops Team to focus on core deployment problems like building best-in-class CI tools, deployment scripts, log rotation and aggregation, debugging tools, etc. which can be reused across all service deployments.

Moreover, this arrangement allows our engineering team to scale. We can add more and more development teams and, as long as we adhere to the rule that every shippable service must be bundled in a Docker image, we add no additional cognitive load to the Ops Team.

Wrapping up

In recent years, “DevOps” practices have risen in popularity largely in acknowledgement of a fundamental truth: the interdependence between software development and IT operations.

In order to put a complex software application into production, there is often a large context which needs to be shared between developers and ops engineers (configuration, operational characteristics, system dependencies, file paths, permissions, etc). DevOps practices recognize this and seek to make operating on that shared context more efficient by eschewing documentation, silos and rigid process in favour of close collaboration and lightweight communication.

While DevOps practices improve the efficiency of deploying a given tech stack, they still imply an ongoing cost which must be paid with every new tech stack that is introduced - more ops engineers.

Docker fundamentally changes this equation. The container model largely eliminates the interdependence between software development and IT operations by radically shrinking the shared context both teams operate on down to the simple concept of an immutable container. This reduces the need for tight collaboration between development and ops and allows us to scale out to new technologies without paying the ongoing cost of needing more ops engineers every time. It makes engineering growth more scalable.

To underline the point, the table below shows the growth of services and tech stacks at GameChanger as a result of moving to Docker.

| Number of services | Number of tech stacks | |

| August 2014 (just after moving to Docker) | 5 | 2 |

| March 2015 | 15 | 6 |

Following our migration to Docker we have tripled the number of services and technologies we support in under 9 months. We also managed to shrink the size of our Ops Team in the process and reassign those engineers to projects which generate revenue.

So, if you’re considering implementing Docker at your organisation, be cognizant not only of the technical benefits it can bring but also the impact it can have on your business’s cost structure and ability to scale if used appropriately.